|

| |

|

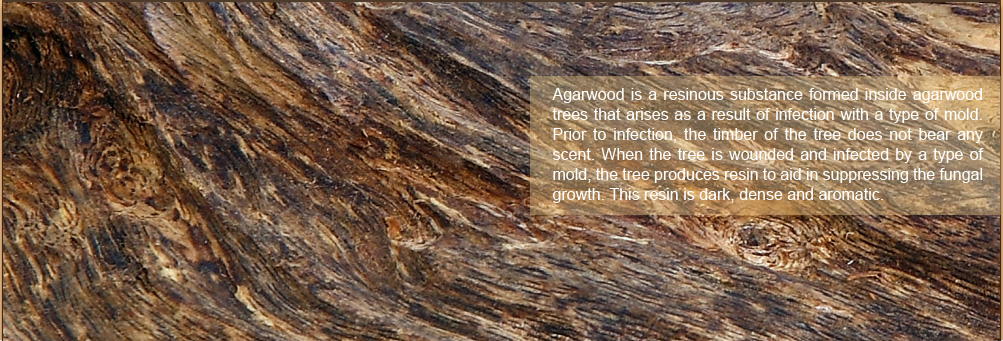

Agarwood is a resinous substance formed inside agarwood trees that arises as a result of infection with a type of mold. Prior to infection, the timber of the tree does not bear any scent. When the tree is wounded and infected by a type of mold, the tree produces resin to aid in suppressing the fungal growth. This resin is dark, dense and aromatic. The resin embedded wood is commonly known as aloes, aloeswood or agarwood. It is known by various names in different cultures: it is known as “chenxiang”, “chenshuixiang” and “shuichenxiang” in Chinese; “aguru” in Sanskrit; “oud” in Arabic; and “gaharu” in Indonesian.

It takes tens to hundreds of years for agarwood to be formed. In addition, in natural environment, only a small percentage of agarwood trees produces agarwood. Hence, agarwood is rare and precious.

[back to top]

Tree species capable of producing agarwood

Agarwood enjoys the title of “the King of Incenses”. Regarded as the most precious kind of wood in the world, it is indeed an extremely rare natural resource. The rich and elegant aroma of agarwood mainly derives from aloewood oil (or agarwood resin). From the perspective of current botany, four families of trees are known to produce agarwood, namely Thymelaeaceae, Burseraceae, Lauraceae and Euphorbiaceae. In response to specific conditions, such as in face of attacks of natural forces or by human beings, which result in wounds and fungal infection, the trunks of these tropical trees will produce resin for self-treatment, suppression of the spread of wounds and other effects of self-protection. The long process, across tens to hundreds of years, by which the resin and wood fibres integrate and transform into resinous agarwood carrying a unique fragrance is known as “incense formation” or “agarwood formation”.

In the view of current botany, four families of trees are known capable of producing agarwood.

Thymelaeaceae: Majority of tress that produce agarwood belong to the genus Aquilaria, which mainly grow in regions in South China, Vietnam , Cambodia , Lao, Vietname, Malysia , Thailand , Burma , India and Indonesia.

Burseraceae: Trees in the Burseraceae family that can form agarwood mainly grow in central South America.

Lauraceae: Trees in the Lauraceae family that can form agarwood mainly grow in central South America.

Euphorbiaceae: Trees in the Euphorbiaceae family that can form agarwood are mainly distributed in the tropics.

[back to top]

Uses of Agarwood

Religious Uses: Agarwood is highly valued and used as offerings by Buddhists, Taoists, Catholics, Christians and Islams.

Medicinal Uses: Medical and therapeutic usage of agarwood is well recognised. It is used as medicine in the old traditions in China, Islam, India, Tibet and South East Asia .

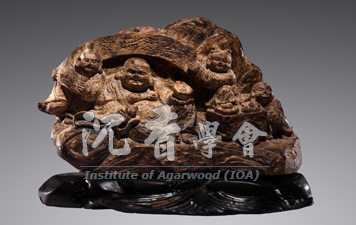

Artistic Uses: The pleasant aroma and rarity of agarwood makes it a precious sculpting material. Large and intact agarwood pieces for creating sculptures are hard to find. Related artworks are relatively small in numbers. Furniture made from large pieces of intact agarwood is hardly seen on the market.

[back to top]

Conservation of Agarwood

Towards the end of the last century, agarwood was listed as a potentially threatened speciesof plant by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES).

Incense and aloes, also known as agarwood, has received the same respect since the beginning of civilization. It's permanent! “Permanency” is an abstract concept beyond time and space. Since ancient times, humans have been in search of the significance of permanency through different faiths and philosophies. Permanent objects and wisdom must endure the test of time and history; they stand for the entire mankind's common desire in pursuit of happiness and faith, bringing about physical and mental pleasure realized via the sublimation of virtues. Fulfilling all such criteria, the incense culture is a noble and elegant culture.

Since the onset of the history of incense culture, humans have mastered the modulation, extraction and medicinal use of incense. For instance, the Arabs and Indians were experts in extracting fragrant oil and balm; the ancient Egyptians invented perfume production; the Chinese applied a variety of incense and spices as medicine in treatments and regimens. The hereditary wisdom of incense culture has carried through the ages, from generation to generation, and this continuity has benefited mankind. Incense culture has evolved together with the history of human civilization. Ethnic ancestors from different faiths and cultural backgrounds have been using the most precious incenses for worshiping Heaven and Earth, paying respect to ancestors, communicating with and venerating the deities, all for exploring the continuation of life and the mystery of permanency.

Accompanying the maturation of incense culture is the rapid and successful development of the craft of incense utensils and tools. Religious ceremonial implements and incense vessels with ethnic characteristics, ingenious utensils for incense appreciation as well as containers for refined perfumes and essential oils have been crafted all over the world – these are important carriers of the permanent heritage of incense culture. Crafts, ornaments and furniture magically carved from rare fragrant materials such as agarwood have passed on this antique cultural heritage in a quaintly elegant manner.

The wisdom and cultures of mankind need to be sustained, and we should be responsible for carrying forward and preserving these important cultural treasures from generation to generation, allowing the incense culture and the profound essence it represents to flourish in the permanency of human history.

[back to top]

Factors for agarwood formation

Consolidating the experience from the past and present as well as information found in Chinese herbal classics, five factors for agarwood formation have been identified, namely “raw formation”, “ripe formation”, “removal”, “insect attack” and “fungal infection”:

“Raw formation”: When wounds are developed or branches are broken due to destruction by natural forces such as windstorms and thunder, animal scratches or logging by men, trees will produce resin to heal its wounds, during which agarwood will be produced. The longer the process, the better the quality of the scented wood.

“Ripe formation”: Trees may wither and die of continual production of resin which leads to blockage of its canals. Over a long period of time, the wood fibres will blend with the resin and solidify into superior hard and dark agarwood which sinks in water. Meanwhile, the life of the agarwood tree is brought to an end.

“Removal”: When the wounded parts of trees come off as a result of infection in large and small pieces, they may contain remnants of resin, which will blend with the wood textures, forming agarwood.

“Insect attack”: Trees that are bitten and attacked by parasitic insects will produce resin for self-protection and healing, and agarwood will be formed as a result.

“Fungal infection”: At the initial stage of fungal infection, the amount of resin formed is very small. However, prolonged infection will engender high quality agarwood.

[back to top]

The accumulated rich experience and wisdom in assessing agarwood have been recorded in books for future reference over the long history of development of incense application in China. Chinese incense classics contains rich and detailed information about the places of origin, appearances and grading of agarwood. Nanfan Xianglu (Records of Nanfan Incense) from the Song Dynasty details various aspects for assessing agarwood ranging from its places of origin, quality, factors for formation, colours and textures to sinking condition. Concerning places of origin and quality, it points out that “Agarwood from Chenla (Khmer, today's Cambodia) is the best, Champa (Vietnam) comes second”. As for the factors for agarwood formation, it suggests: “Raw formation is the best, followed by ripe formation”. Its comments on the colours and textures of agarwood are that “The hard and black are the best, followed by the yellowish”.

In addition, “fragrance, quality, shape and colour” also provide the basis for appreciating agarwood. “Fragrance” obviously refers to the aroma, whose quality is of foremost importance given that agarwood is a scented product. A good fragrance is pure yet rich and permeating; it is far-reaching and enduring with delicate changes when burned. Regarding “quality”, it depends on the condition of the aromatic resin stored in a piece of agarwood which gives the wood fragrance; therefore agarwood with rich and quality resin content receives a higher ranking. “Shape” and “colour” are standards for assessment taking into consideration the shape, colouring, grain as well as the distribution of resin in a piece of agarwood. The ancients examined agarwood through debates and competitions, evincing that comparisons based on real objects and accumulation of experience are the only ways of determining its quality.

[back to top]

Agarwood from various places and related grading systems

The formation of agarwood is attributed to a complex web of environmental factors including the species of the tree, climate, soil, effects of fungal stimulation, position of formation, duration of formation as well as shape and size. Due to variations in objective criteria, the assessment and grading of agarwood is a broad and profound topic of study. Until today, a comprehensive and internationally acknowledged set of standards for assessing and grading agarwood has yet to emerge. Therefore, assessment still relies on the experience and knowledge of experienced members of the industry, and variations in grading systems may occur even within the same region, for example, between the levels of wholesaling and retailing. The standards for grading agarwood differ among countries:

Malaysia: Mainly divided into twelve grades, including the six grades “Double Super”, “Super”, “A”, “B”, “C” and “D”, in which “A” and “B” are subdivided into two sub-grades, “C” is subdivided into four sub-grades and “D” is subdivided into two sub-grades.

Grade: Double Super, Super

Grade : AA, A, C

Indonesia: Mainly divided into nine grades, with the first four being “Super A”, “Super B ”, “Super C ” and “ Sabak ”. The rest are graded according to the amount of resin content and the size of the wood piece.

Grade: Super A

Grade: Double Super, C, D

India: Mainly graded as “Triple Super”, “Double Super”, “Super”, grades A, B, C, D and etc. (information provided by a member of the industry in India)

Vietnam: Due to the wide distribution of agarwood produce, five grades have been established according to the places of production from the North to the South. Kinam is classified by four grades.

Grade: Top-class

[back to top]

The King of Agarwood – Kinam

There was a popular ancient saying: “The nidanas from performing good deeds in three life-spans are rewarded with smelling the fragrance of Kinam in the present life”. Renowned as “the King of Agarwood”, Kinam is the best of all agarwood species and is known by numerous appellations – “Qinan”, “Kynam” and “Kannam”, while the Japanese refer to it as “Kyara”. The ancients used the saying, “Good agarwood is particularly hard to obtain” to describe Kinam owing to the rare probability of its formation, which makes it all the more precious. Until today, a scientific account of the real factors for Kinam formation is not yet available. However, deducing from ancient Chinese incense literature, it is likely to be related to parasitic and nesting activities of insects and bees, which subject the scented wood to prolonged absorption of honey and milky substances that gradually blend with the resin produced from the tree, resulting in a lengthy process of transformation. In addition, some modern scholars hold the views that it is caused by fungal stimulation that transforms the nature of the scented wood or by genetic changes in the fragrant trees.

Types of Kinam

China has great accomplishments in incense literature. Xiang Sheng (A History of Incense) by Ming collector Zhou Jiazhou categorizes Kinam according to the conditions of its formation, such as “green formation”, “sugary formation”, “honey formation”, “raw formation”, “golden silk formation” and “tiger's skin formation”. Haiwai Yishuo (An Overseas Leisurely Account) grades Kinam by its characteristic colours, with such categories as “warbler green”, “orchid formation”, “golden silk formation”, “sugary formation” and “iron formation”. In modern times, Kinam is graded and categorised as “white Kinam”, “green Kinam”, “red Kinam”, “yellow Kinam”, “purple Kinam” and “black Kinam”. Besides, the mountainous regions in northern Binh Thuan Province in Vietnam are famous for Kinam production, with its local produce classified into the four categories of “white, green, yellow and black”.

|

|

|

|

|

| White Kinam |

|

Green Kinam |

|

Khmer purple Kinam |

|

|

|

| Black Kinam |

Kinam decorative pieces |

[back to top]

|

|

|

|

|

|

Copyright © 2013 www.agarwood.hk. All rights reserved.

|